Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:20 — 51.9MB)

Listen with your favourite player Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | RSS | Subscribe

In this article, we will explore the phenomenon of unethical leadership. Why do oil drilling firms dump production waste in the Amazon?1 Why do airline manufacturers hide potentially catastrophic faults from their customers?2 Why does big tech use behavioural psychology to take advantage of young developing brains? And why do car makers hide vehicle emission data from the public?3 At the core of these breaches is unethical decision-making by business leaders with concern for profit at all costs. Unethical Leadership results from a skewed sense of priority, a heightened sense of self-importance, and malevolence toward the welfare of people and the environment. In this article, I'm sharing details of the Ford Pinto case from the 1970s, highlighting what a lack of ethics in leadership looks like, how it impacts people's lives and what we can do about it.

Unethical Leadership in Business

It never ceases to amaze me as I go about my day the extent to which businesses large and small go in their attempt to get one over on the buying public. It seems to be a game of cutting as close to the bone of ethical practice as possible without getting caught. The implicit marketplace script appears to say; “let’s take advantage of people and make as much money we can while giving as little value as possible to the customer. And sure, if we get caught, we’ll just apologise and pony up. In the meantime, let’s make enough money so we can cover the legal costs. If people are hurt by what we do, it’s their fault. After all, it’s just business.”

From cleverly packaged meat products that hide small portions under the label, containers with fake bottoms, high-margin lower quality goods placed at eye level, to discounted fruit and veg that go off within a couple of days. Every time we go shopping, it takes effort not to be conned. And it’s not only foodstuffs; appliances and personal technology have built-in obsolescence. Social and other technology apps mine us for our information without our knowledge or consent. Tradespeople who take outrageous shortcuts. Financial products are created so that the providers don’t lose. You can even buy books showing you how to build products that manipulate and exploit people’s propensity toward addiction.

People Care For People, Corporations Don't

Everywhere you look in our wondrous capitalist society, people and organisations take unfair advantage and make unethical decisions in the name of profit. Corporations exist to make a profit, and that’s fine, but to what extent will you go in your business to achieve that profit? For many corporations, large or small, a sense of humanity and ethical behaviour take second place in the decision-making process. Like it or not, and call me a cynic if you will, this is the state of play that the “survival of the fittest” capitalist ideology encourages. At its worst, as we will see in our example with Ford, people become fodder for profit cannons. Of course, people care for people, but within a faceless and soulless organisation driven by the profit model, people lose their sense of humanity. It's a pseudo-reality where concern for their fellow human being is not a factor.

Read more articles on Leadership

Learn To Become An Effective Leader

These 21 Leadership Tips are derived from established leadership theory and practice and are designed to help develop both the self awareness and recognition of others you need to build a successful organisation. Find out more and download your free copy.

Unethical Leadership & The Ford Pinto Case

Academic literature and popular media are littered with examples from trivial right through to downright psychopathic, where decision-makers have disregarded their sense of humanity and social obligation for the sake of duty to the corporation and bottom line. The story of the Ford Pinto is a case in point.

In 1968, executives at the Ford Motor Company put the low-cost Pinto into production. To have their new vehicle ready for the 1971 market, Ford decided to reduce their design-to-production time of three years down to two. This straight away perhaps compromised established protocols for safety. However, commercial pressure for a low-cost vehicle was significant, so they powered on. Before production, Ford crash-tested various Pinto prototypes to assess fire risk from road traffic collisions and to meet the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration standards. The prototypes and the Pinto final design all failed the standard 20-mph test, resulting in ruptured gas tanks and fuel leaks. The only Pintos to pass the test had been modified somehow, for example, with rubber bladders in the gas tank or additional reinforcement.

“From cleverly packaged meat products that hide small portions under the label, to high-margin lower quality goods placed at eye level, to discounted aged fruit and veg that goes rotten within a couple of days. Every time we go shopping it takes effort not to be conned.”

Ford Knew There Was A Problem

Ford executives knew the Pinto design was flawed and represented a serious risk to human life in rear-end collisions, even at low speeds. However, the commercial pressure from Japanese competition took centre stage in decision-making. Should they go to production with the existing design and risk consumer safety? Should they delay production, redesign the gas tank and concede defeat to foreign competition? Remarkably, Ford not only committed to the flawed design, but they stuck to it for the next six years. The decision to proceed with the Pinto production without safety improvements led to more than 500 cases of fire-related deaths, fifty lawsuits, and many millions in compensation to families, not to mention the trauma inflicted on the victims' families.

Why would anyone do this?

Why, when you have hard evidence – when you know your actions will likely lead to human suffering and even loss of life – would you proceed along the same lines? I believe that situations such as these account for human beings' propensity to subjugate themselves to the power system they occupy. When basic psychological needs are not provided for, self-protection and fear set in. In that setting, their sense of self is entirely dependent on the system, so to forgo the system's rules amounts to forgoing their sense of self. Internal dialogue insists that if one breaks the rules, then their very existence is threatened. Regardless of the psychological process at work, it seems clear that to make decisions in a fake plastic setting, such as the world of business, we must leave our humanity at the door.

In the Ford Pinto case, evidence suggests that executives relied on cost-benefit reasoning to analyse the expected monetary costs and benefits. Apparently, Ford's costs for making these safety improvements were only $5 to $8 per vehicle. However, the executives reasoned that this outweighed the benefits to Ford and the public of a new tank design. It seems the risk of loss of life was not part of their decision-making model.

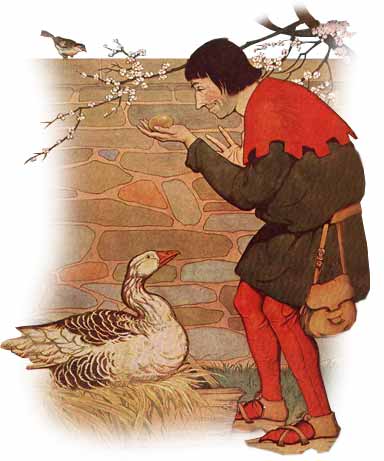

There was once a Countryman who possessed the most wonderful Goose you can imagine. For every day he visited the nest, the Goose laid a beautiful, glittering golden egg.

The Countryman took the eggs to market and soon began to get rich. But it was not long before he grew impatient with the Goose because she gave him only a single golden egg a day. He was not getting rich fast enough.

Then, one day, after he had finished counting his money, the idea came to him that he could get all the golden eggs by killing the Goose and cutting it open. But when the deed was done, he did not find a single golden egg, and his precious Goose was dead.

The Art of Self-deception and Disregard for Ethics in Business

Cognitive bias distorts decision-making. And the “rational” approach in business circles, coupled with a host of complex psychological factors, fuels this distortion. The moral and ethical imperative didn’t even enter the equation for the Ford executives. A phenomenon known as “ethical fading,” detailed by Ann Tenbrunsel and David Messick, has highlighted how self-deception is a central component in unethical decision-making. In their 2004 paper4, the authors wrote;

“Self-deception allows one to behave self-interestedly while, at the same time, falsely believing that one’s moral principles were upheld. The end result of this internal con game is that the ethical aspects of the decision “fade” into the background, the moral implications obscured.”

Self-deception

Tenbrunsel and Messick suggest that self-deception is an unawareness of the internal processes that lead us to form opinions and judgments of ourselves and events in which we are involved. This self-deception involves avoiding the truth, lying, and keeping secrets from ourselves. The practice is widespread, normal, and accepted in the lives of everyone we know. We create the lives we live through the stories we tell ourselves. And these stories allow us to do what we want and then serve to justify our actions. Over time, there exists what psychologists call an “ethical numbing”. This is where repeated exposure to an ethical dilemma numbs our sensitivity to our own unethical behaviour. Unless we are willing to monitor and question our own thoughts, assumptions and behaviour, we are in danger of cultivating unethical practices in our organisations.

What role did the organisational culture at Ford play in these unethical decisions? Evidence suggests that the vice president at the time, Lee Iacocca, who was closely involved in the Pinto launch, did not encourage a safety culture. A mentality of “just get it done” filtered down from the top through the entire company. A 1977 magazine article5 quoting an engineer from Ford, wrote that any employee who dared to slow progress would have been fired on the spot. Safety wasn’t a popular conversation around Ford in those days, and with Iacocca, it was taboo. Apparently, whenever staff raised a concern that resulted in a delay on the Pinto, Iacocca would chomp on his cigar, look out the window and say, “Read the product objectives and get back to work.”

Learn To Become An Effective Leader

These 21 Leadership Tips are derived from established leadership theory and practice and are designed to help develop both the self awareness and recognition of others you need to build a successful organisation. Find out more and download your free copy.

Is Unethical Leadership OK in Your Organisation?

Breach of the ethical imperative is not isolated to the Ford Pinto and Lee Iacocca case. At that time, lobbying by the motor industry against safety legislation was at its height. At Ford, they saw safety as meddling in free enterprise. The motor industry insisted that accidents were not problems caused by cars but by people and road conditions. Yes, with the sobriety of fifty years; hence, we may see how crazy that idea is now. But it wasn’t necessarily crazy then — not to the industry. Consider how we do business today; how might our decision-making assumptions be flawed or unethical? Are we considering others' welfare in the products and services we create, or is that none of our business?

Consider the technology sector, for example — it’s the wild west as far as regulation goes. The creation of addictive digital applications that take advantage of children and sleepy people is widespread and accepted in the corporate world. There are even books that show you how to do it6. And what’s worse, their authors seem completely unapologetic in their promotion of these unethical practices. What's worse again is that the media and some academics have become their champions. The authors even go so far as to suggest that it’s okay to deceive people, but only if we believe it’s in their best interests. Of course, the authors assume that they know your best interests. That usually means their best interests, not yours.

“Over time there is what psychologists call a sort of “ethical numbing” where repeated exposure to an ethical dilemma numbs our sensitivity to our own unethical behaviour”

Rationalising Our Actions

It takes a special kind of psychology to compartmentalise one’s thoughts to the extent where it’s ok to manipulate, deceive, and contribute to the misery of another human being. A self-interested, manipulative, self-oriented person, unable to accept responsibility for their own actions or feel remorse, would be branded a psychopath. According to the Canadian professor of law, Joel Bakan, this is what corporations have become7.

For me, it’s quite simple; if I know what I’m doing is hurting or has the potential to hurt someone, then I should stop. There are plenty of ways to make money and live a comfortable life without knowingly hurting other human beings in the process. But then again, if you’re mind has become consumed by self-deception in this regard, then the justification of unethical and nefarious behaviour is sure to follow. To think this way, to rationalise unethical behaviour, one has to disconnect from their humanity.

“The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops we’ve created are destroying how society works. No civil discourse, no cooperation; misinformation, mistruth. And it’s not an American problem — this is not about Russians ads. This is a global problem.”

Chamath Palihapitiya

How To Cultivate Ethics In Business

I can’t throw stones without taking ownership of my own flawed thinking and unethical behaviour in business. There have been times when my actions have been less than admirable. I’ve taken profit at the expense of quality and turned a blind eye to less-than-satisfactory work carried out on my behalf. Pressure to perform, turn a profit, or even break even tends to make human beings act unethically. That’s the inherent problem with the neoliberal capitalist profit-driven system.

In a 2016 article for Harvard Business Review 8, Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at the University of California, wrote that powerful people are more likely to engage in unethical leadership behaviour than those with less power. Keltner’s 20 years of research in human behaviour has shown that while people usually advance to authority positions through positive behaviours such as empathy, fairness and collaboration, these qualities fade with time. A sense of privilege and selfishness seems to take over many business leaders. He suggests that iconic abuses of power, such as that at Enron and Lehman Brothers, are extreme examples of unethical leadership. All companies, large and small, are susceptible.

So what can we do about it? Keltner has some suggestions.

Make Time For Self-reflection

The first step, Keltner suggests, is developing a greater sense of self-awareness and appreciation that our thoughts and actions can have far-reaching consequences. Meta-cognitive studies in neuroscience9 has shown that thinking about our thoughts and reflecting on our feelings and emotions can give rise to greater control of our actions. For example, recognising feelings of euphoria, joy, and confidence can engage parts of our brain that help us keep irrational behaviour in check. It also helps with negative feelings such as anger and aggression, which can often be facets of unethical leadership and poor decision-making.

Keltner suggests that we can build this self-awareness through daily meditation and mindfulness practices. Research shows that even just a few minutes each day spent in a quiet space focusing on repetitive breathing patterns, for example, can lead to greater focus, control, and calmness under pressure. We can practice this throughout our day too. For example, in between tasks, take time to close out that last task by pausing for a few minutes. Take a few deep breaths, and think about the next task and how you would like it to go for you and others. Then proceed.

Practice Empathy, Gratitude, & Generosity

Working with corporate executives, Keltner emphasised the importance of human factors. Empathy, gratitude, and generosity, he says, have been shown to sustain benevolent leadership. These attributes of leadership, when executed authentically, bring about a sense of unity in the team or organisation. They suggest that someone cares that we are a part of something important and good. Ruling with an iron fist might get things done but at what cost? Keltner suggests that expressing appreciation, showing tolerance and understanding, and simple generosity acts lead to higher employee engagement and productivity.

Keltner suggests that to cultivate empathy, gratitude and generosity, entrepreneurial leaders should;

- Listen with your ears, eyes and body. Put the blinkers on, so to speak, convey genuine interest and engage.

- When someone comes with a problem, try to empathise with the language of understanding. Take on board what’s being said and void knee-jerk reactions.

- Recognise good work when you see it, no matter how small. Send them an email, or better still, say it face to face.

- Publicly acknowledge the work someone has done.

- Delegate high-level responsibilities.

- Avoid taking the credit — be humble and be inclined to give that credit to others.

Some Final Thoughts on Unethical Leadership

I’m for working for oneself over being an employee. I believe there are few better means by which human beings can develop themselves professionally, technically, and personally. Working for oneself brings great fulfilment, even if it proves to be the greatest challenge you have ever undertaken. It affords us the freedom to be creative and innovative without the boundaries of organisational structure. We get to create our own boundaries. We direct our own energies and command our own work. Self-employment, entrepreneurship in its purest form, insists that we take responsibility for ourselves. But it also insists that we consider how our work impacts other people. This is a kind of socially-minded entrepreneurship, one that curiosity and interest in the work drive rather than profit extracted from the labour of others.

When the ends become so important as to justify the means, we know we have lost our way. Money and profit should never be the reason to enter business IMO— if they are, it won’t last. A sustainable way of life comes from an honourable starting point: the work itself, the service, and the product. The joy must be in the work itself and not the material ends — the applause, reward, status or power. When money becomes the aim, as we have seen in the example above, all kinds of insane justifications creep into our decision-making. Self-deception takes over, and unethical practices are not far behind.

Our Motivation to Enter Business

Why do we go into business? What is it about the entrepreneurial idea that attracts us? Is it money, control, status, or power? Is there something so absent in us that we are prepared to spoof, tell half-truths, and manipulate people toward our own ends? The term “unethical behaviour” seems sterile when we see the extent to which our lack of humanity can go for the sake of profit. It just doesn’t seem to capture the tragic and painful reality that transpired for hundreds of people due to Ford’s cost-benefit analysis in the Pinto case. I believe it doesn’t need to be this way.

The capitalist imperative is a very strong field of force, and once it captures us, there is every chance we might lose ourselves. Sure, go into business for yourself–pursue your personal and business goals–but never lose sight of your humanity. The Ford Pinto case serves as testimony to the obscenities we bring about when we forget who and what we are.

References

- Boutrous Jr, T. J. (2012). Ten Lessons from the Chevron Litigation: The Defense Perspective. Stan. J. Complex Litig., 1, 219.

- Cruz, B. S., & de Oliveira Dias, M. (2020). Crashed Boeing 737-max: Fatalities or malpractice? GSJ, 8(1), 2615-2624.

- Rhodes, C. (2016). Democratic business ethics: Volkswagen’s emissions scandal and the disruption of corporate sovereignty. Organization Studies, 37(10), 1501-1518.

- Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (2004). Ethical fading: The role of self-deception in unethical behaviour. Social justice research, 17(2), 223–236.

- Dowie, M. (2021). Pinto Madness. Retrieved 14 February 2021, from https://www.motherjones.com/politics/1977/09/pinto-madness/

- Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked, (p. 167). London: Penguin Books.

- Bakan, J. (2020). The new corporation: How” good” corporations are bad for democracy. Vintage

- Keltner, D. (2016). Avoiding the Behaviors That Turn Nice Employees into Mean Bosses. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2016/10/dont-let-power-corrupt-you

- Fleming, S. M., & Dolan, R. J. (2012). The neural basis of metacognitive ability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1594), 1338–1349.

[…] Unethical behavior might also be more prevalent with narcissistic leaders, as they prioritize self-interest above the greater good, potentially engaging in fraud or exploitation to achieve their goals. […]