Elite performers in all fields of work, sport, and the arts, possess psychological skills that allow them to reach a higher level of output than almost everyone else. Research reports that psychological skills training, comprising techniques and strategies for self-regulation, mental preparation & recovery, is an essential component of high-level achievement. So, if we want to excel, we must adopt and perfect these psychological skills. In this article, we will explore five important psychological skills required for elite performance. We'll offer support from empirical research, and suggest ways by which you can develop these skills yourself, whatever your work or sport. OK, let's retrain your brain

Introduction

I wish I had known and understood these concepts when I was a younger man. I'm 48 at the time of writing, and it seems I needed to live half a lifetime or more and make a million mistakes before the penny dropped. The idea that we can't know before we know seems accurate. What's important to understand with psychological skills training, is that it's not a magical system to get the perfect career, fame, or commercial success. These things might be important to you, and you may even realise them, but the associated satisfaction is usually short-lived. Something else is asked of us, and it is our job to find out what that is. The following practical techniques may, perhaps, help you in that search.

What Is Psychological Skills Training?

Psychological Skills Training is a methodological system that performers use to manage and regulate their psychological state. It is effective both in and out of the performance environment. Robert Weinberg and Daniel Gould, in their book, Foundations of Sport & Exercise Psychology, define psychological skills training as follows; “Psychological skills training (PST) refers to the systematic and consistent practice of mental skills for the purpose of enhancing performance, increasing enjoyment, or achieving greater sport and physical activity self-satisfaction’’ (Weinberg & Gould, 2007, p. 250) 1. We can, of course, apply these skills beyond sporting domains and across the entire breadth of human living. Therefore, to achieve personal success in life and work, we must be focused and committed to refining this mental skill set.

In recent times, focus on psychological skills has become prominent throughout sport, business, the arts, military, emergency services, and indeed popular culture. As such, concepts are often open to misinterpretation, misrepresentation and an interchange of distinctly different concepts. Robin Vealey, in The Handbook of Sports Psychology (2007) 2 suggests a distinction between the desired outcome (increased self-confidence, enhanced focus & attention, and self-regulation) and the psychological means by which we advance the desired outcomes (mental imagery, self-talk, meditation).

In this sense, the psychological skill is the learned ability to carry out a specific performance task. The means or “technique” is the procedure we use to develop the capacity within us. Cognitive restructuring, self-regulation, mental rehearsal, self-talk, and goal-setting are prominent mental techniques psychologists and coaches use in interventions with clients. Multimodal PST combines these basic techniques (see below for more on this concept).

Multimodal Psychological Skills Training

In multimodal psychological skills training, psychologists employ multiple techniques combined and tailored to a performer's specific requirements. Programs consist of (1) assessment, (2) education, (3) acquisition, (4) practice, (5) integration, and (6) review. The assessment phase gathers information about the individual, desired outcomes, who, what, when and where interventions should be undertaken. Appetite and confidence in the system of training can also be assessed.

Once gathered, the psychologist teaches the performers the chosen techniques. At the education stage, we also help performers understand how and why these techniques work and employ resources such as diaries, worksheets, and videos to reinforce learning.

The performers' acquisition of skills comes in a safe environment without the pressure of assessment. After the individual achieves competence, we integrate the skill into practice routines. Then comes integration, where the performer actively employs the learned techniques in competitive or work situations. In the final step, we evaluate and update the program to ensure its effectiveness.

For more on this subject, see The Oxford Handbook of Sport & Performance Psychology 3.

Free Download: Retrain Your Brain

Many of us operate on autopilot. The conditions of our lives shape our thoughts, feelings, and actions, what's possible for ourselves and whether or not the world is supportive. Retrain Your Brain is a 5-step process, once practiced daily can allow us take back control.

Psychological Skills of Elite Performers

There are many ways we can examine psychological skills and many ways we can offer for their enhancement. Regardless of the domain of work or play, what we are really trying to achieve is a broader means of coping with change. We have discussed Resilience at length in a recent article, and indeed, it is resilience and our ability to bounce back from adversity that we seek to develop. At work, in sports, business, and careers of all types and in all domains, we are subject to the changing environment. Therefore, we must learn to self-regulate regardless of the conditions we face. Developing and refining our psychological skill set helps us do just that. The following five mental skills are common among practitioners working with clients.

1. Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive Restructuring is a method therapists and applied psychologists use in interventions to help clients restructure or reframe their negative experiences. Most of us react to difficult conditions automatically and with very little control over where our mind goes. The momentum of automatic negative thinking can carry us away into very dark places, or, we can stop ourselves and choose another direction of thought. In basic terms, cognitive restructuring is about changing your mind about a given experience.

Cognitive Restructuring was developed from Richard Lazarus' Cognitive Meditational Theory of Emotion (Lazarus, 1991) 4 which suggests that our cognitive appraisal of a given situation creates an automatic assessment and response. Lazarus states in his paper “When we say that emotion affects cognition, we are saying, in effect, that thoughts are also part of the emotions they cause.” This means that we can change the way we feel by changing the way we think about what happens to us.

How To Apply It

Self-defeating thoughts and responses to challenges kill creativity, innovation, and problem-solving ability. They are, in large part, habitual–we learn them. Therefore, we can unlearn them. Cognitive restructuring asks you to change your response, so instead of accepting the first thought that enters your mind, such as “I can't do this” or, “I'm failing”, or, “everyone thinks I'm useless”, choose the opposite. Say, “I can do this, I just need more practice”, or “I'm getting this”, or “my friends are rooting for me, I know it”. If you find yourself in the heat of action, dramatically failing and beating yourself up, then it's too late. The work must be done before the need arises. This takes time, practice, and a safe place to develop and often requires a coach to help you navigate.

Practical Suggestion

When things don't go according to plan, give yourself a break. Stop, and ask yourself, does this response serve me, make me stronger and more capable? If the answer is no, chose a statement that does. Don't wait for the big day to arrive, and hope that things go well. Practice when you practice.

2. Self-Regulation

Self-regulation refers to our ability to regulate both positive and negative arousal. The anticipation before a game or presentation, fighting the urge to stay in bed rather than go training, or managing anxiety about one's technical ability. Self-regulation is about self-control both inside and outside the game, overcoming the stress of high-pressure situations and the anxiety of performance.

Human performance studies have defined arousal as the psychological and physiological reaction to conditions and assume an optimal state of arousal for high performance. The combination of thought, emotion, individual preferences, and technical aspects of the task determine this optimal level of arousal 5. Research suggests we can exercise control over our state of arousal. However, fear plays a big part (Kellmann et al., 2006) 6

The Fear of Failure

Anxiety-based fear is essentially an internal reaction to an event that hasn't yet happened and may not. This is distinct from the fear you might experience in an immediately threatening situation such as a robbery or a house fire. Therefore, anxiety-based fear is irrational. Anxiety-based fear reduces our motivation, negatively affects our self-confidence, volition, focus and attention, and plays a significant role in activating the sympathetic division of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). You may notice you become nervous, your hands become sweaty, your heart rate increases, and you can't think straight. In the heat of the moment, your skills seem to desert you, and you may even become frozen to the spot. It's what has become commonly known as the fight-or-flight response.

Fight or Flight

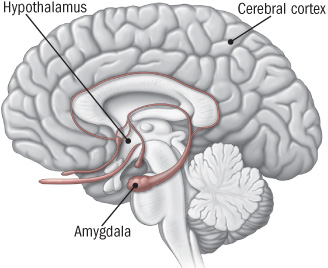

When we experience negative stress, the amygdala, the brain's emotional centre, becomes highly active. The prefrontal cortex responsible for decision-making shuts off. So too does the hippocampus, the area of the brain responsible for learning and memory. We quite literally, can't think straight. We're on autopilot. (Image courtesy of Harvard Health)

The flight-or-flight pattern of negative anticipation and response has taken time to bring about, and it might be such an integrated part of your life experience that tracing it to its origins is impossible. Regardless, it became established through continued repetition, and as such, you can establish a new pattern of thought and feeling regarding your skills and ability.

How To Apply It

Our ability to self-regulate in a given setting can be impacted by a difficult day at work, a poor diet during the day, or challenges in other areas of life. Psychological skills training offers a number of strategies, including some of those mentioned in this article. Self-talk, positive imagery, short periods of rest and relaxation, pre-performance routines, and mental rehearsal strategies.

Practical Suggestion

To counter the negative impact of anxiety about an event or poor motivation to practice, try these tactics;

- Get an accountability partner, a colleague or a fellow athlete that you respect. Be there for one another as a source of motivation.

- Ensure you are properly fuelled throughout your day. Glucose depletion has been shown to negatively impact mood and performance.

- If you're feeling drained, unmotivated or stressed, take a 15 min rest. You may find an improvement in mood afterwards.

3. Mental Rehearsal

When we imagine something, a scenario of either past or future context, there is more going on than merely the visual component. There is a physiological component–we feel it in our body. There is an emotional component too. By merely sitting on our couch at home and imagining a past experience or the possibility of a future one, we can bring on a complete psychophysical experience. Empirical research recognises this, and in domains of human performance, we can use our mental rehearsal capabilities to prepare for the demands of performance in work and sport. Just as physical training prepares the body for the demands of performance, mental rehearsal does the same.

Visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, and speech, may all be involved in the mental rehearsal process. The performer becomes completely immersed in the mental image of the task without being present in the usual performance arena. As well as building proficiency in a given task, mental rehearsal provides a safe environment where a performer can execute a task, build confidence, and manage anxiety. The underpinnings of this process have been observed in the activation of the same neural networks as that observed in the actual performance itself 7. We can literally fool our bodies into believing we are there.

How To Apply It

Two-time Winter Olympics gold medal winner Lizzy Yarnold in her 2014 interview with the British Daily Mail, said every night when she went to bed, she visualised her event. In fact, not only did she visualise it, she felt it too. Interestingly, and perhaps critically, she said she didn't visualise winning. Instead, she visualised the process. I believe this is a key aspect that should be borne in mind in mental rehearsal. It is a matter of prioritising processes over outcomes.

Practical Suggestion

Before setting out on your day, before breakfast and before anything else imposes on your time, take a few minutes to imagine the process of your routine. See it, feel it, hear it – allow every aspect of the performance play out in your mind and see it go as you wish it to go. Do this also at night before you retire. Create positive anticipation.

Eastern philosophies have held for thousands of years that the present moment, free from judgement and classification, is key to the realisation of self to the highest level. These ancient philosophies ask us to drop the mental conversation, the incessant and automatic inner dialogue and accept conditions for what they are. Science, in recent times, has begun to catch up with this idea.

Mindfulness-Based Therapies

Mindfulness-based and acceptance-based theories and interventions, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) 8 and Mindfulness Acceptance Commitment (MAC) 9 have dramatically changed how psychologists think about how best to help people in their work and sport.

Acceptance-based and Mindfulness-based approaches view our response to internal states, such as cognitions, emotions, and physiological events, rather than the experiences themselves, as fundamental to performance outcomes. In other words, it's more to do with managing our response than changing the external event.

4. Self-talk

We refer to self-talk as inner speech or dialogue. It is the conversation that mostly goes on within the dome of the skull and it refers to statements we address to ourselves. They may be deliberate but more often than not they are automatic and reflect beliefs, concepts and ideas we hold about ourselves and the world around us. Self-talk can reflect a positive attitude toward oneself (I'm good at this) or a negative (c'mon, don't mess this up). However, our interpretation of the words uttered is often distinctive and personal and more important to understand than the literal meaning.

You might say to yourself, for example, “this routine is hard”, yet you are empowered to do better in spite of the stress. Your colleague or teammate uttering the same statement, on the other hand, might give up. So it's not the words that matter, it is rather the feeling tones associated with the words.

According to research, self-talk can be used in different forms and has different functions for different people. Therefore, it also has different performance effects (Hatzigeorgiadis et al., 2007) 10. We are encouraged, therefore, before implementing a program of psychological skills training, we should first take into account the requirements of the domain, the level of participation, and the particulars of the individual. We may also need to consider the cyclical nature of the work being undertaken.

How To Apply It

I coach a juvenile football team in my local club, and one of the things I constantly encourage them to do, is to be kind to themselves when things don't work out. I ask the boys to mind their mental conversation, and instead of accepting their first internal response, choose words that they would like to hear. Also, as we train together, we give them short word groups that act as positive cues. These include “attack it”, “get there”, “my ball”, “light as a feather”, or, “aggression”. These terms establish positive meaning in the competitive setting and cue a behaviour.

Practical Suggestion

As with all these strategies for improved performance, you must practice. Throughout your day, in work, with family, and when you're alone, notice how you speak to yourself inside your own mind. When you hear automatic unhelpful responses and commentary, ask yourself if they are helpful. If not, change the response. Instead of reacting automatically, become a conscious agent.

5. Goal Setting

I believe goal setting is not all it has cracked up to be. It is not, as some often suggest, a means by which we may design our own future experiences. Life is inherently unpredictable. So rather than using goal-setting as a rigid tool to obtain something, it should instead be a guide to our actions. A raft of research has identified goal setting as an effective strategy across performance tasks, groups, methods, and performance settings. However, recent research suggests the benefits of goal setting have been overstated (Ordonez et al., 2009)11

Goal setting seems so straightforward. Make your goals SMART; Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound and you're away in a hack. It's a cute acronym, but it is often misleading. In Goals Gone Wild, researchers identified specific negative side effects of goal setting. These included neglect of non-goal areas of life, distorted preferences for risk, rise in unethical behaviour, inhibited learning, damage to organisational culture, and reduced intrinsic motivation. Therefore, we've got to carefully think through any psychological skills training program incorporating a goal-setting element.

How To Apply It

Many factors influence the implementation and the success of any goal-setting strategy. Personality, perceived ability, environmental factors, peer support and coaching support significantly influence the motivation and behaviour of the performer. Therefore, goals have to be unique to the individual. My approach is somewhat different to the likes of SMART goal setting. Let's take an athlete for example.

The athlete knows their sport, and they know what the pinnacle of achievement at their particular level in that sport is. Therefore, we don't have to set that as a goal – it's set already. Now, whether they believe they can achieve it or not is a different matter. So, the only goal worth setting is the goal to focus on the task at hand. It is the drill we are practising now, the set of drills comprising this element of the training session. In this, we build momentum in the right direction.

The athlete must stay present and compete with only themselves in this particular drill or exercise at this particular moment. All thought and pursuit of externalised goals take them out of the only moment they can be effective. The cumulative effect of this process over time is they reach exceptional levels of performance. Building momentum is the key.

Practical Suggestion

This method may seem too simplistic, or even unscientific. However, it is based on the finding that the traditional means of setting goals can operate counter to how we think they do. They can destroy motivation and kill creativity. Therefore, my encouragement to you is that you stay in the moment. Your only goal should be to perform this task better than you did yesterday or ten minutes ago. Stay present, get in the zone, and do your thing. One day you'll wake up and realise the compound effect of all your efforts.

In Conclusion

Psychological skills are important tools for not only work or sporting success but for life itself. They bring us beyond the ends achieved or dreamt of, leading to broader self-awareness, heightened self-efficacy, self-worth, and personal development. They can enhance our coping skills and our ability to bounce back from adversity, and they can give us a deeper empathy and relatability to other people.

A Self-Determined Approach

The most important ingredient in high performance and the realisation of success (however you may define it) is interest and curiosity. It is my strongly held view that if we are low on curiosity and high on a sense of duty, then we have more struggle than fun. What I mean is, that if motivation is primarily extrinsic, then our time in the game won't last. This doesn't mean a sense of duty cannot spur us on–it can. We may internalise and adopt extrinsic factors as our own, otherwise known in self-determination literature as “introjected”, “identified”, or “integrated” regulation. For more on these concepts, see Deci & Ryan (2000) 12.

What we try to achieve or experience in all of this effort towards superior performance, is self-realisation. Who am I? Who are you, beyond this thing you do? This is the ultimate question that we all eventually have to answer. In the end, people will remember us for how we made them feel, not for what we did. Medals, awards, accolades, recognition and applause count for nothing if we fail to know ourselves. The route to this, I have found, is to immerse yourself in the work for its own sake, for the joy of it. If you do, you'll have lived a life worth living, and your achievements will be a reflection.

Leave a Reply